During the course of the Demystifying the Abbey project, a number of previously unrecorded sites of archaeological interest have been identified on land once held by Abbey Cwmhir. It is not possible to date them with any precision and hence attribute them to the Cistercian period. However, their form suggests a medieval origin and it is plausible that they were in use during the, approximately, 350-year period between the foundation of the Abbey in the late 12th century to its dissolution in 1536 during which time the Abbey Cwmhir was under Cistercian rule.

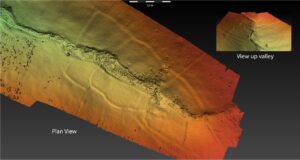

The shape of an open enclosure on the sheepwalk at the northern end of Cwmffwrn farm was clearly revealed by drone photography. This area is within walking distance of the Abbey and so more likely to be under its direct management. The enclosure consists of a much-eroded, earth bank on three sides of an irregular rectangle measuring around 33m long by 27 at its widest, the fourth, shortest side being open. It is joined to a small platform which is at a lower level, just above a spring. It is likely that a simple shepherd hut once stood on the platform. When in use the bank would have been surmounted by a wood-woven “fence” such as seen in illustrations of medieval farming, while removable hurdles would have closed the wide opening. (See earlier posts for examples of the illustrations.)

The shape of an open enclosure on the sheepwalk at the northern end of Cwmffwrn farm was clearly revealed by drone photography. This area is within walking distance of the Abbey and so more likely to be under its direct management. The enclosure consists of a much-eroded, earth bank on three sides of an irregular rectangle measuring around 33m long by 27 at its widest, the fourth, shortest side being open. It is joined to a small platform which is at a lower level, just above a spring. It is likely that a simple shepherd hut once stood on the platform. When in use the bank would have been surmounted by a wood-woven “fence” such as seen in illustrations of medieval farming, while removable hurdles would have closed the wide opening. (See earlier posts for examples of the illustrations.)

Basically, the enclosure offered the means of holding sheep, (more likely in this context than cattle), in proximity to a shepherd. It might be relevant that the sheep would be held away from the main enclosures/fields of the nearby farms lower down the valley.

The actual role of the enclosure is a matter of conjecture. However, a number of possibilities arise.

- Overnight protection of the flock: Rather than taking the flock down to overnight on the arable fields below, the flock might have been brought together for protection within the sheepwalk. This raises the question of protection from who/what, with the obvious answer of other humans, or from wild animals. Both are possible though protect from humans is possibly less likely as the alternative of driving the sheep down to field nearer the farmsteads would seem to be more secure. If from animals then the most likely predator would have been wolves. Since wolves were eliminated by at least 1500, this explanation would date the enclosure firmly within the Cistercian period.

- Segregation: The enclosure is probably too small to contain all the sheep using the sheepwalk so might have been used to segregate a portion of the flock away from the rest. This could be in response to the frequent disease pandemics, murrains, affecting sheep in the Middle Ages.

- Concentration: At various times of the year sheep need to be concentrated in one place for purposes of husbandry, for example during shearing, milking or lambing. The entire flock would not need to be collected together and confined at the same time, just enough for, say, a day’s work or otherwise for a short time, before they were released back onto the pasture. In the case of shearing, the proximity of the stream would benefit not only the shepherd(s) but could have been needed for the washing of fleeces.

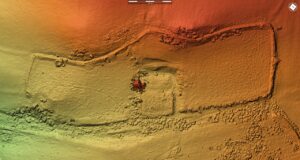

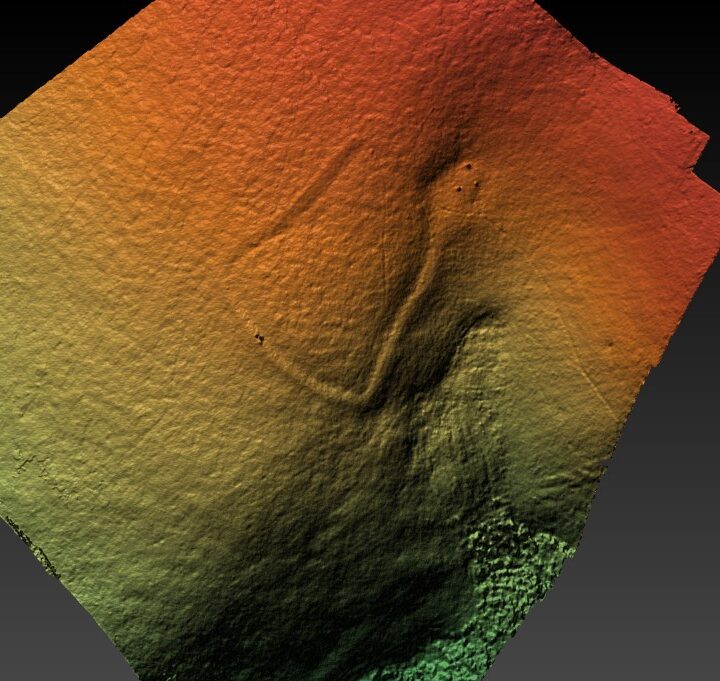

A very different set of earthworks exist in a steep valley off the Cefndyrys sheep walk. Here a number of enclosures, together with a platform, are set alongside the stream. The number of enclosures appears to have increased over time, each new one being added to the previous. There are also indications of earlier enclosures beneath the ones most clearly visible. Cefndyrys, like Cwmffwrn, is within walking distance of the Abbey and provides an extensive upland sheepwalk.

A very different set of earthworks exist in a steep valley off the Cefndyrys sheep walk. Here a number of enclosures, together with a platform, are set alongside the stream. The number of enclosures appears to have increased over time, each new one being added to the previous. There are also indications of earlier enclosures beneath the ones most clearly visible. Cefndyrys, like Cwmffwrn, is within walking distance of the Abbey and provides an extensive upland sheepwalk.

The enclosure system is around 300m of Groes. Groes is usually described as an incursion onto the common. However, its scale is different to the smaller, later incursions, and suggests that it was the centre of extensive sheep farming operations on Cefndyrys. It is also well placed for routes down to the Abbey with links in other directions to a nationwide network.

The enclosure system is around 300m of Groes. Groes is usually described as an incursion onto the common. However, its scale is different to the smaller, later incursions, and suggests that it was the centre of extensive sheep farming operations on Cefndyrys. It is also well placed for routes down to the Abbey with links in other directions to a nationwide network.

Also worthy of note is that the stream feeds the Fishpool in the main valley below which could have implications for the washing of wool.

I am currently minded to consider the enclosures, Groes and the open land of Cefndyrys together as a single purpose, upland sheep “ranch”, probably without the benefit of a significant proportion of arable land as was common with most other farmsteads. As such it could only have existed as part of a wider system of farming such as provided by the Abbey holdings.

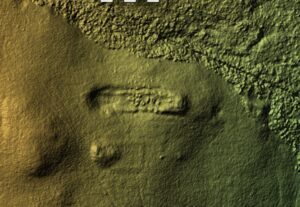

Another feature of medieval sheep farming is the sheepcote. One exists on the sheepwalk associated with the Abbey Grange of Dolhelfa. This grange is specifically mentioned in the charter, 1199, of Roger Mortimer granting lands to the Abbey. It consists of arable lands in the Wye valley and upland pasture on the adjacent hill, Drysgol. Either within, or immediately adjacent to, the granted land is a sheepcote. Early OS maps mark it as a deserted chapel, while later accounts considered it to have been a long hut. It is now identified as a sheepcote. There is possibly another sheepcote next to it but vegetation cover precludes our confirmation at this time. These long narrow buildings provided sheltered accommodation for sheep and may have been introduced by the Cistercians.

Another feature of medieval sheep farming is the sheepcote. One exists on the sheepwalk associated with the Abbey Grange of Dolhelfa. This grange is specifically mentioned in the charter, 1199, of Roger Mortimer granting lands to the Abbey. It consists of arable lands in the Wye valley and upland pasture on the adjacent hill, Drysgol. Either within, or immediately adjacent to, the granted land is a sheepcote. Early OS maps mark it as a deserted chapel, while later accounts considered it to have been a long hut. It is now identified as a sheepcote. There is possibly another sheepcote next to it but vegetation cover precludes our confirmation at this time. These long narrow buildings provided sheltered accommodation for sheep and may have been introduced by the Cistercians.

It is clear that medieval farming has left many marks in our landscape, some of which are a legacy of the Cistercians of Abbey Cwmhir. As the project progresses, we hope to identify other extant remains and so fill out the picture of the Abbey’s influence on our landscape.

This comment is posted on behalf of Maureen Lloyd and takes content from an email she sent following my April talk to the Trust. It refers to an article: Sheepcotes: Evidence for Medieval Sheepfarming by Christopher Dyer, 1995.

This is truly fascinating and I must admit although the name Sheepcote is familiar we have a farm called that in the Wye valley I have never considered the housing of sheep. It is clear they would have been housed by night as sheep are notorious for not being good animals kept indoors for long periods. Sheep farmers go on the system that sheep are born to die, they will do it randomly even in 21st century! The article obviously centres on the Cotswolds which was a predominate sheep rearing area. It mentions sheepcotes all over England but there is no mention of Wales, having said that often things spread over the border and Wales is forgotten.

Reading it from a certain knowledge of sheep and the differences between English and Welsh living I think we need to be very careful about taking everything the paper mentions on board. It does seem to highlight that a lot of the sheepcotes were close to villages or deserted villages, while as I understand it in Wales we were not much for villages maybe partly due to the terrain maybe we didn’t get on with the neighbours that well! It talks about distant meadows being used for hay and quotes 13km which by Welsh standards I would have thought was actually quite close so again it is difficult to transplant the sheep systems from Gloucestershire to Radnorshire. But I have learned a lot, and it did say that it wasn’t only lords that built sheepcotes but peasants would have used them as well probably on a smaller and less elaborate scale. It also seems to suggest that they went out of use, after about 1500. I think and that would have been as a result of diminishing returns for the wool, I suppose. It does mention that the Cotswolds were second only to the Welsh Marches in wool production however I suspect it would have been the eastern part ie Shropshire, Herefordshire rather than the Welsheries.

This comment is posted on behalf of Rhiannon Powell.

Thanks very much for the papers, Julian; quite a lot for me to digest from the discussion, as I’m not from the Abbeycwmhir area and don’t know the geography, (I grew up, and live, about 8 miles south of Leominster, where the 13th century Benedictine Priory acquired much of its wealth on the backs of the Ryeland sheep, hence the reference to the pre-eminence of the Marches sheep trade – and indeed Ryeland wool was later said to be Queen Elizabeth 1st’s favourite for her stockings!)

I suspect that the Cistercians would have brought good knowledge of sheep rearing with them, and have kept up to date with changing practice through their connections with other monasteries across Britain and Europe. I wondered about the availability of water, which I think you have now answered, because it would not have been possible to overwinter sheep, or lamb them, in a location without a good water supply; overnight might have been more possible. However, one thing that seems to me to go against the outlying structure being a sheepcote is the dimensions – if I remember right, it was a rectangle but nowhere near as elongated a one as all the sheepcotes described appear to be. I think the reason for the elongated structure is that the sheep would be kept in smaller pens subdividing the structure, which would need to be easily accessible by the shepherd – in other words, long rows of pens, with a walkway down one side, or in the middle between two rows of pens.

The idea of the structure being for rounding up the sheep and holding them for fleece washing does make sense.

I haven’t yet read the other two papers, Julian, but will make time to go through them in the next couple of days. (As I’ve said, I’m certainly not an expert on mediaeval farming practice, or on Abbeycwmir, and can do no more than speculate…)